Seattle’s newly appointed public health authorities had good reason to be concerned in the late summer and early fall of 1918. The so-called Spanish Flu was ravaging lives and communities around the globe, claiming literally millions of victims—and had begun its rapid march across the United States. Flu, of course, was then as now an annual event in the lifecycle of cities and people. But this time it was different.

The influenza epidemic of 1918-19, known popularly as the Spanish Flu, would be the worst pandemic of modern times. It was the first outbreak of the H1N1 influenza virus, effecting hundreds of millions of people before it ran its course—with perhaps as many as 10% of those infections becoming fatal, resulting in one of the deadliest disasters in modern history.

In addition to its unusual scale, the outbreak was different in another way: While most influenza outbreaks disproportionately kill juvenile, elderly, or already weakened patients, the 1918 pandemic predominantly killed previously healthy young adults. Modern research, using virus taken from the bodies of frozen victims, has concluded that the virus killed through an overreaction of the body’s immune system. The influenza particularly affected those between the ages of 20 and 35 whose robust immune systems exhausted themselves in the fight against the disease. The resulting battleground ravaged the lungs, and for many led to secondary and often fatal infections from bacterial pneumonia.

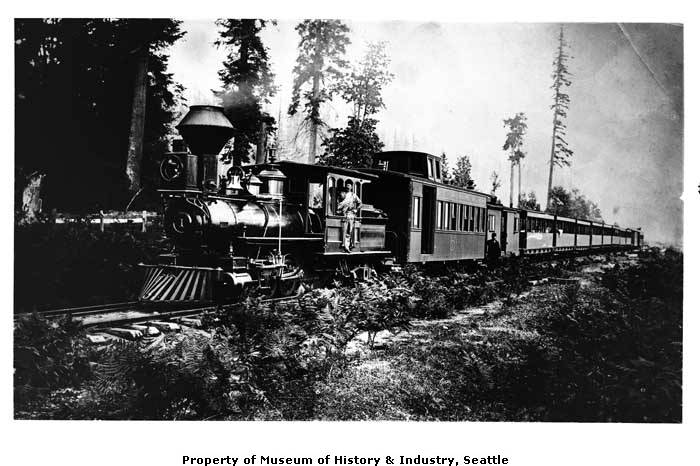

No one is really sure, even now, how or where the flu started. Did sick pigs in Kansas somehow infect European- bound US troops in 1917? Did avian flu affect soldiers in the European trenches? One recent historical theory is that infected labor contractors arriving in Western Canada in 1917 traveled from Vancouver across North America by rail, and thus launched the flu on its global pathway.

One place where it did not start? Spain. It was called Spanish flu only because neutral Spain escaped wartime censorship and gave it more publicity than other countries, including reports that King Alphonso XIII was gravely ill (while reports of President Wilson’s illness were largely hidden).

At any rate, a world at war—with mass movements across long distances, crowded living conditions, poor sanitation and stressed out health systems— created a global Petrie dish. An initial wave of flu in the spring and summer of 1918 sickened so many European soldiers that German Gen. Erich von Ludendorff blamed the disease for helping foil his last offensive, which stalled just 37 miles from Paris. Entire divisions were laid low by illness, and in confusion each side accused the other of germ warfare.

By the time a second, more lethal wave of the flu struck the world in August and September of 1918, American reinforcements were turning the tide of the war. But these same troops would not escape the flu, and the ending of war only seemed to hasten the spread of the disease as troops headed back home, haunted by the battlefront and many infected as well.

The flu arrived full bore in the Unites States in Boston on August 31, 1918 with returning American soldiers, and quickly spread to major cities like Philadelphia, where it then booked passage to Puget Sound the following month on a trainload of sick Navy draftees.

Having had time to witness the spread of the epidemic across the United States in the fall of 1918, neither Seattle nor Washington State officials were under the delusion that the disease would miraculously skip the Northwest. The hope was rather to identify and isolate early cases quickly enough to prevent the rapid spread of the disease, thereby keeping influenza from becoming epidemic.

But the deck was stacked against Seattle—and those cards would be played very soon. The Spanish Flu likely slipped into Washington on Sept. 17, when those feverish Naval recruits from Philadelphia docked at Bremerton’s Puget Sound Naval Shipyard. In Bremerton, Navy officials cancelled all dances and ordered the men to keep away from social gatherings of any kind, and shortly thereafter prohibited all visitors. But the flu was here—and already spreading.

Less than a week later, 173 people were reported stricken with what was described as severe influenza at Camp Lewis south of Tacoma—although at first Army officials refused to label it Spanish Flu and insisted on inviting some 10,000 civilians to the base that week to watch a review of the troops. But when the sick soldiers began to develop pneumonia, Army officials placed Camp Lewis under quarantine, prohibiting anyone from entering or leaving the base.

But that too was too little, too late. Within days, the disease appeared in Seattle—a densely populated, rapidly industrializing city of more than 300,000 souls, mobilized for war and filled with troops, war workers, crowded streets and close housing conditions.

From the start, city Health Commissioner McBride and his counterpart in the state Department of Health, Dr. Thomas Tuttle, watched the situation carefully– and with growing anxiety. McBride had no real way of knowing the trajectory of the epidemic. But when 200 influenza cases were suddenly reported at the UW Naval Training center in Seattle on September 28, McBride’s worst fears had come true.

On October 4, city newspapers reported that one cadet had died of influenza and that 700 more were ill– 400 of them in the hospital under treatment and observation. Publicly, McBride maintained optimistically that there were no civilian cases, no cause for alarm, and that the outbreak among the cadets was only a routine form of flu.

But the optimism lasted less than a day, after two influenza-related civilian deaths were reported in the city that evening. The next day, October 5, after meeting with Mayor Ole Hanson, McBride officially confirmed that the Spanish Flu had made its way into Seattle and that if not contained would soon flash through the city’s civilian population like wildfire.

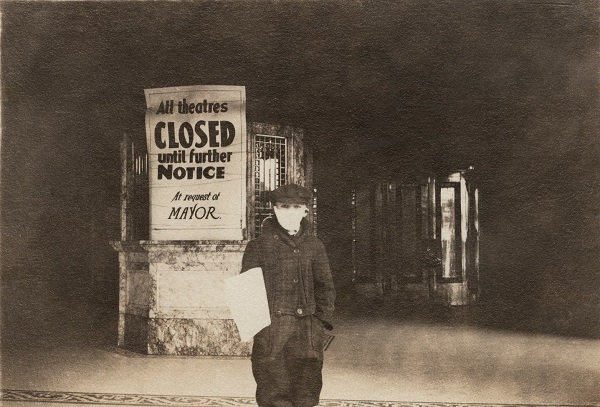

The Mayor and Commissioner took immediate action. That very day, they shut Seattle’s schools, theaters, dance halls, gyms and churches. And they did not stop there. They simultaneously prohibited all private dances, declared that streetcars and stores had to be well ventilated, and ordered police to enforce the anti-spitting ordinance with utmost strictness.

Mayor Hanson even warned that more widespread closures of public places might be forthcoming if the disease were not quickly checked. As the Post-lntelligencer put it, city officials had been “aroused at last to the imminence of the danger facing Seattle.”

When people awoke on October 6, 1918, the city felt different—and it was different in ways that perhaps have never been repeated until now. Church services were cancelled; theaters, poolrooms, libraries were closed; entertainment in cafes and restaurants was prohibited; and all businesses allowed to remain open were required to prevent crowding.

Public schools were also ordered closed, despite the fact that School Superintendent Frank Cooper believed that Mayor Hanson was acting hysterically over the situation, and besides which the Mayor should have asked the Superintendent’s opinion before closing schools, stating that in any event “it is a senseless thing to do.”

Superintendent Cooper wasn’t alone in his anger. The suddenness of the closure order came as a surprise to many. The Mayor’s office was flooded with calls from clergymen asking if they could hold services. The answer was a resolute NO: According to Mayor Hanson, “religion which won’t keep for two weeks is not worth having.”

Society women inquired whether planning for their charity events should continue. Theater owners protested they were not consulted; had they been allowed to remain open, they reasoned, they could have been the centerpiece of a citywide public health education campaign. Now all they could do was refund money to angry patrons.

And so it went. For days, newspapers and the public lambasted Hanson and McBride for issuing the closure order without advance warning. There were exceptions to the general outcry of course. Children were said to be cheering all across the city at the unexpected vacation. Gas station owners enjoyed something of a bonanza as well-off residents, with little else to do, took to their cars and motored along Seattle’s parkways and into the countryside. And in any event, it was smart to keep moving–the police chief created a special “Influenza Squad” to enforce the ban on social gatherings. “Some will kick,” Hanson said stoically, “but we would rather listen to a live kicker than bury him.”

Hanson and McBride were convinced the closure order would have an immediate and salutary effect, and as October wore on, and the bans stayed in effect, things did get better. Hanson, in particular, believed that the ordeal would be over shortly thanks to these measures. The Mayor also engaged in a little wishful thinking: he claimed that many who believed they had influenza really did not or simply have a less virulent strain. With adequate cooperation from the public and with enforcement of the orders by the police and the health department, Hanson was confident that the epidemic would be over within five days. And in an attempt to exercise what we might today call an “abundance of caution,” at the last minute he added weddings to the list of prohibited gatherings and limited funerals to 15 minutes.

Mayor Hanson was of course wrong. In no large city in the United States was the epidemic over in just a few weeks. As Seattle cases mounted, McBride told the public that the city would be better served if influenza patients came to a public hospital, where the work of the nurses could be carried out more efficiently than it would be in a private home. (In other cities, health officers frequently asked people with mild cases to remain at home under the care of a family member, thus freeing up hospital beds and nurses for those who were more severely ill.) Nurses—women for the most part—played a large and important role in treating the illness, as did the Red Cross, which coordinated necessary medical supplies and assembled the gauze masks that would soon be a ubiquitous sign of Seattle’s war on flu.

One factor that came into play in Seattle that distinguished it from other cities was that we had some time to plan, and that planning was largely conducted in the context of what we might now call the military-industrial complex. As home to the large Bremerton Shipyard and the massive private shipbuilding industry (which was largely occupied with government contracts), Mayor Hanson was determined to work closely with the industry to protect its work force—and its production and profits. After all, Seattle shipyard workers accounted for some 30,000 men, nearly 10% of the city’s population.

McBride knew that it would be difficult to keep this workforce healthy during the epidemic. “With an army of men as large as we have together in the shipyards it is very difficult to keep the disease from spreading should it gain a foothold there,” he told reporters early on, even before it arrived, clearly reflecting his concerns and the Mayor’s directives. The solution: fast action by the City’s health laboratory and Navy doctors to develop a flu vaccine that would be developed solely for the benefit of the shipbuilding work force.

To protect this “army of men,” McBride proposed the inoculation of each and every one of these workers with one of the several anti-influenza serums that were developed. “Let no question of money or men interfere with your work,” was Mayor Hanson’s order. By October 11, the city had produced enough doses of the anti-influenza serum to inoculate nearly every shipyard worker. Requests from all across the region came in for the vaccine but Seattle officials refused each of them (except for one from Fort Worden in Port Townsend).

McBride was open in his reasoning: “Seattle needs all the serum we can grow and we will share with nobody until our shipyard workers have been properly inoculated.” He was convinced of its effectiveness, citing its initial use at the Bremerton yard where only three mild influenza cases had developed among the 3,000 sailors who had been given the injection, and claiming that no one in the city who had been given the two doses of the serum as required had contracted influenza.

Despite that track record, the serum by itself did little to halt or even slow the spread of the epidemic among the general population in Seattle, and by mid- October nearly 3,500 cases had been reported.

Newspaper coverage was matter-of-fact and blind in its optimism. Deadly disease was more common than today, and war news pushed most flu stories to the inside pages. Health authorities were quoted day after day as hoping the pandemic had peaked, weeks before it actually did.

Yet news of apocalypse crept in and kept upsetting the predictions of the experts. McBride, with his high confidence in the serum and in the various anti-crowding measures, increasingly blamed private citizens for the frustrating continuance of the flu. “Influenza is still spreading through the carelessness of persons who insist upon violating the rules laid down to arrest its progress,” he said.

To drive home the point that the epidemic was serious business, McBride issued orders for stricter enforcement of public health laws. On October 18, with backing from the Mayor, McBride ordered the arrest of the proprietor of any soda fountain, ice cream parlor, or restaurant that failed to use hot water to wash dishes and utensils. Police blotters were full of names of those charged with spitting in public and congregating, including twenty-two men arrested for crowding in city pool halls and hotel lobbies. The Police Chief declared that repeat offenders would be dealt with severely.

On October 22, McBride announced that the peak of the epidemic had been reached, and that while the number of deaths would likely continue to rise for the next week or so, the number of new cases would decline. Unfortunately, once again the optimism was misplaced. The very next day new case reports showed an increase in the epidemic, and the numbers continued to grow ever larger in the following days. Exasperated, McBride threatened to close all businesses except pharmacies and food stores. Doctors and nurses at the emergency hospital were so over-worked and short-staffed that McBride himself volunteered.

But McBride insisted that stronger anti-crowding and isolation measures were necessary. Even if the officials had to shut down Seattle completely. And that is exactly what he and Mayor Hanson threatened if residents did not do more to help bring an end to the disease.

Complaining that people were walking about downtown on the weekends when they should be at home avoiding crowds, he declared that if residents were to stay home for two days it would “do more to stop the epidemic than all the doctors in town.” Failure to check the disease immediately, McBride announced, would result in the same terrible outcome Eastern cities had faced earlier in the Fall. And he had no intention of letting that occur, he announced, even if it meant resorting to even more drastic measures.

McBride made good on his promise. On the morning of Monday, October 28, Mayor Hanson and Commissioner McBride issued a sweeping set of additional public health orders, the centerpiece of which was a mandatory flu mask order to go into effect the next day.

On October 29, 1918, six-ply gauze masks became mandatory in Seattle. The next day they were required throughout the state. Anyone shopping at a store, boarding a streetcar, or in any situation where one he or she could come into contact with another person in public was required to wear a mask. Streetcar conductors were told to admit no passenger who was not wearing a mask. When told that conductors hesitated to discriminate against passengers based on clothing, Hanson bluntly told commuters that they best get a hold of one of the Red Cross’s 250,000 masks as soon as possible “or tomorrow morning they will walk to work.”

The city did not stop with masks. Making good on earlier threats, McBride closed all ice cream parlors and soda fountains in the city until further notice and forced at least the two-day closure of all shops and stores for the weekend of November 2-3. After that, all stores and offices were prohibited from opening before 10:00 am or closing after 3:00 pm, in order to prevent crowding on streetcars during the rush hour commute for shipyard workers. Although the stalls of the city’s Pike Place Market were allowed to remain open, McBride warned residents not to crowd the area. “We have given notice that we don’t want the people downtown… and no matter whom it may inconvenience it will be necessary to use the police to keep crowds moving,” he announced. If people needed to buy groceries, they could do so at their local, neighborhood store, he added.

Draconian? Yes. Unpopular certainly. But at last it seemed to work—cases did begin to modulate in early November and Seattle’s flu situation slowly improved. Nevertheless, despite extraordinary pressure, McBride and Hanson were reluctant to remove the closure order, let businesses return to their normal hours, or allow residents to remove their masks for fear that the epidemic would take a sudden turn for the worse. “There seems to be no doubt that the situation has materially improved,” Hanson told the public on November 10, but added that he “was not prepared to say just when we can relieve the city of the restrictions.”

But like the best laid plans, life interfered and public health discipline fell apart completely when the Armistice was announced the very next day, November 11, 1918. Thousands of joyous people in this classic Homefront City celebrated in the streets, with, the papers reported, “not a mask in sight.” Indeed, the mask rule was lifted the very next day and theaters and public places reopened at once.

With the war ended and the closures lifted, there was a lot to celebrate and throngs of people packed downtown for days (and nights), filling theaters to see performances such as “My Soldier Girl” at the Metropolitan and “The Race of Love” at Pantages. The Ford sisters, called “the greatest dancing pair on the Orpheum Circuit,” were performing at the Moore. The owner of the Oak Theater had taken time during the closure to renovate his theater, and now re-opened with a musical comedy. Crowds of patrons waited in line at the movies and by noon most movie houses had to warn patrons that theaters were at standing room only. As the Post-lntelligencer put it, “the public threw its masks in the stove, piled the breakfast dishes in the sink and hit for town on the first available street car.”

These large-scale celebrations and the crowding of downtown streets and businesses did not seem to have much of an effect on the flu figures, and the numbers of new cases continued to dwindle during the remaining days of November. By early-December, however, the disease seemed to be making a comeback. This time, McBride wasted no time. He warned the public to remain vigilant and to take precautions. The medical inspector for Seattle’s public schools ordered all pupils thoroughly examined, prohibited the assemblage of students, and instructed staff to send any child home who was ill.

Worried that a second wave of the epidemic was hitting Seattle, on December 2, Hanson and McBride took yet another step that they feared might be viewed as too severe but felt necessary—and drafted a resolution requiring the quarantine of all suspected cases of influenza.

The change in attitude reflected McBride’s opinion that the disease was making its way back into the community via outsiders arriving by boat and train. He believed that if these suspected carriers could be quarantined, Seattle might be spared another round without having to resort to a new set of closures. Presenting his case before an emergency session of the City Council on December 5, McBride told members of how fifteen men from cheap lodging houses were recently removed to hospitals. All had been severely ill for several days, but no one had contacted a physician. Under the new rule, the lodging house owners would be required to contact the Board of Health in such cases. The City Council passed the quarantine resolution.

Health inspectors were soon busy quarantining homes. By noon the day after the City Council passed the resolution, more than 100 placards had been posted. The health department was quickly flooded with phone calls from physicians and private citizens reporting cases. By December 10, nearly 1,000 placards had been posted on Seattle homes.

Residents, perhaps worried that the gathering bans and public closures they had come to detest might be enacted again, seemed eager and willing to do anything to help the Health Department rout the disease once and for all. In the public schools, attendance was more than fifty-percent below normal enrollment, in part due to illness but largely because worried parents kept their healthy children home. School officials considered closing the schools completely as a result of the low attendance.

Ultimately, this proved unnecessary, as the second wave passed by late December. Only small numbers of new cases and deaths were reported through the winter of 1919, and only ten patients were recuperating in the city’s emergency hospital on February 28. In March 1919 no deaths from influenza were reported. As suddenly as it appeared, Seattle was now suddenly largely free of the flu (although in late 1919 a milder wave of illness briefly revisited the city in one last bounce).

When the world returned to normal that spring, people awoke as if from a bad dream, perhaps unaware that they had lived through the single greatest American health disaster since European disease nearly wiped out Native American populations in the 19th century. By late spring of 1919, when the numbers finally were tallied, more than 1,500 people had died in Seattle alone, according to Census Bureau estimates.

Statewide, more than 6,500 people were counted dead– more than the state lost in World War I, more than the state lost in WWII, and more than the toll of the Pearl Harbor and the World Trade Center attacks combined. The number of dead in the United State in that period exceeded 700,000—perhaps as many as 50 million worldwide.

Simply put, the Spanish Flu pandemic killed more people in a shorter time than any disease in world history. It reached into every corner of the globe, annihilating villages in Alaska and killing one out of five people in Western Samoa. Before it was over, it is estimated, 3-5% of the world’s population was lost. Compared to that devastating toll, Seattle fared relatively well. Seattle suffered a death rate from the disease approximately half that of San Francisco and a third that of Philadelphia and Baltimore.

On December 31, 1918, in the first official assessment of the tragedy, the city health department blamed the spread of the epidemic on several sources. “Handicapped by routine red tape at first, later by the careful physician (careful not to report his cases), the ‘Doubting Thomas’ of the laity, and in many instances by gross neglect on the part of persons having the disease in a mild form— because of all this the loss of life, health and happiness has been appalling.”

The cause of flu was unknown in those years — the virus itself wasn’t isolated for decades—and as a result, most of the measures Seattle took to fight the plague were largely conjectural. Dramatically, the city concocted its own flu vaccine, based on bacteria found in the dead and inoculated thousands. Yet the serum did nothing to ward off or lessen the disease in the larger population. Gauze masks were equally unlikely to contain or intercept viruses far smaller than the weave, although they may have contained some cough spittle.

But fast and decisive action did make a difference. What may have helped most was the Mayor’s decision to close public gathering places, particularly schools and theatres, despite its political unpopularity. Seattle did have a lower rate of infection than cities where crowds persisted too long. And the use of strict quarantine was likely important even though the state health authorities refused to exercise the same order on a statewide basis.

Over the years the Spanish Flu episode has been called the forgotten epidemic. A pandemic that would cause round-the-clock media coverage today received surprisingly subdued press attention in 1918-1919. Its impact on lives was personal and profound. But rather than monuments or reflections in literature, the flu became a mostly hidden personal story, while the larger public story was largely forgotten. Future novelist Mary McCarthy, for example, was 6 when her flu-stricken Seattle family boarded the train on Oct. 30, 1918, to visit Minneapolis.

Shortly after arrival, both parents were dead, a bereavement that sent her to two different homes of relatives and forever shaped her experiences and her life as a writer. There were a million American stories like McCarthy’s, yet most went publicly unrecorded. There is no Angels in America and few classic works that reflects the experiences of what might be called the Spanish Flu generation—the young adults who bore the brunt of the worst plague in American history.

Most likely the Great War itself, the Bolshevik revolution and the tumult and economic dislocations of the post war years became indistinguishable from the flu as contributing factors to the great global upheaval that shook the world to its very foundations a century ago. But as with so much history, the relevance for today is unmistakable—and essential for us to understand.

As we are experiencing now with Coronavirus, in an increasingly connected world, facing the effects of global warming, deforestation that puts humans in contact with new animal diseases, urbanization, population growth, air travel and shipping of food supplies around the world, great global health challenges will be part of our future. The real question is will we have learned from these past experiences, including our current crisis, to address the next challenge in the most effective and humane way possible. And that history of has yet to be written.